A Case Study on the Importance of Continued Collection Inventory

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

June 25, 2020

Have you ever stumbled on something in the back of your closet that you haven’t seen in years? Maybe you know how it feels to rediscover an old favorite in the midst of spring cleaning. Though the Museum’s collection storage is definitely better organized than my personal wardrobe, the collection department occasionally “rediscovers” precious artifacts when we do inventory.

Since the Museum’s storage holds over 28,000 works of art and artifacts (and an additional 55,000 historic records) there are many opportunities to find works that have been misplaced or mis-labelled. Let me describe one of my favorite rediscoveries in Museum storage: a collection of over 450 mid-19th century clipper cards that were made right here in Lower Manhattan.

What is a clipper card?

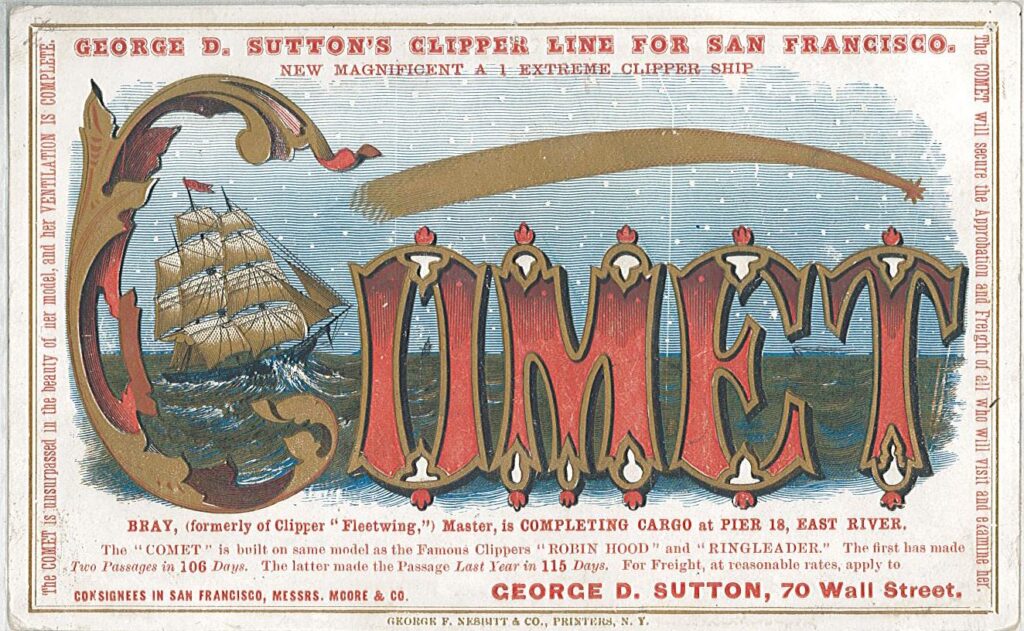

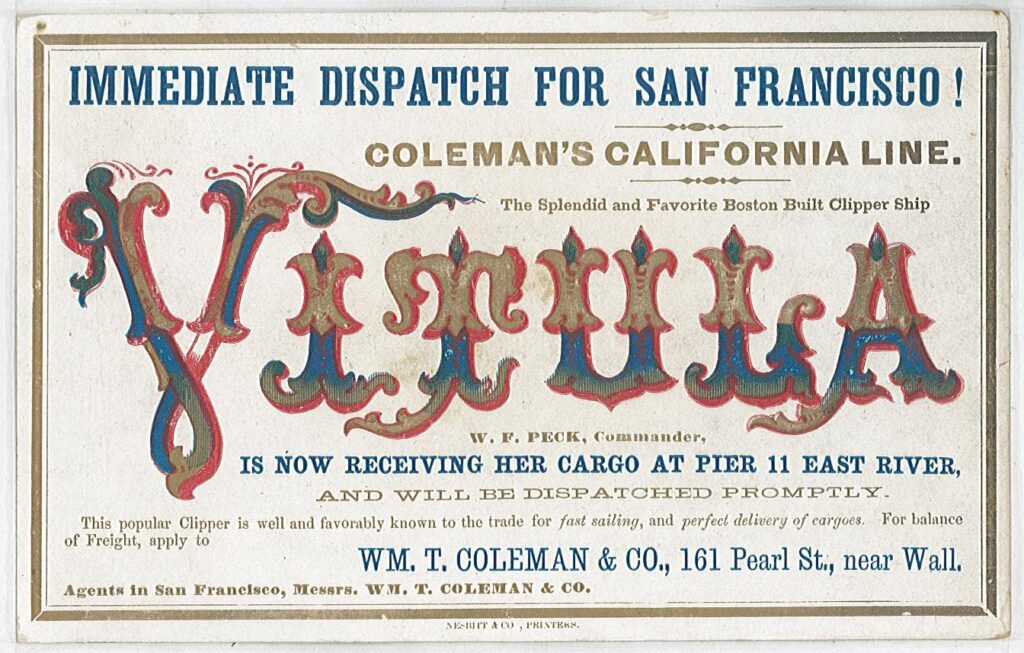

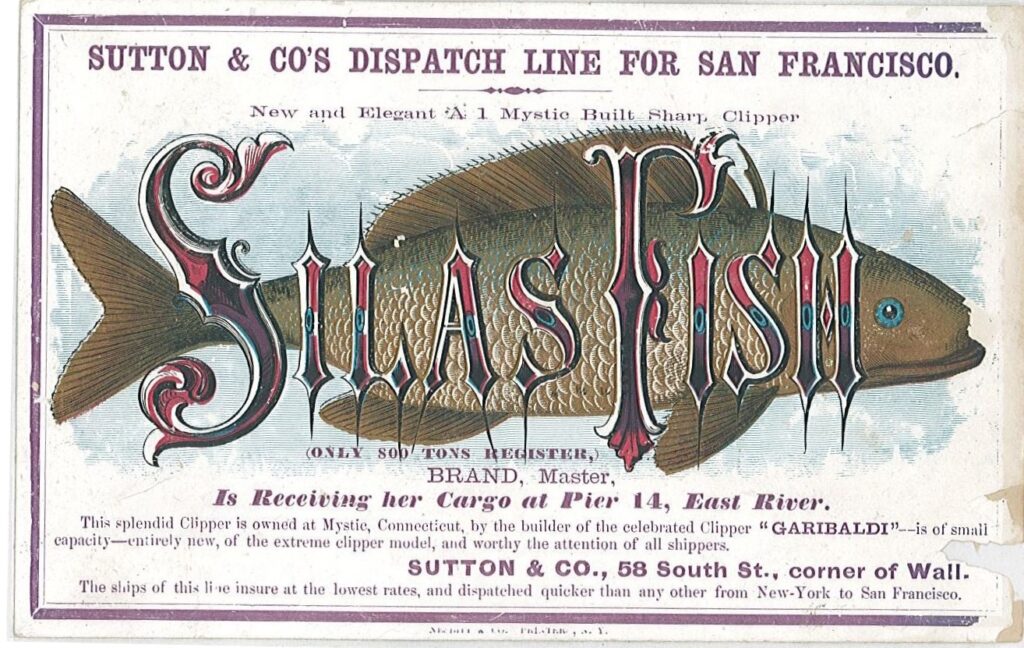

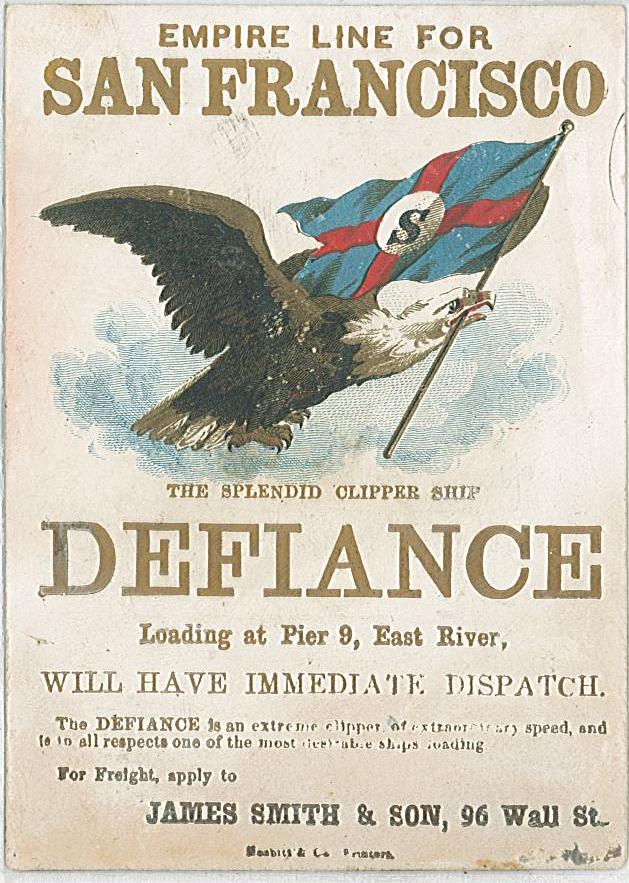

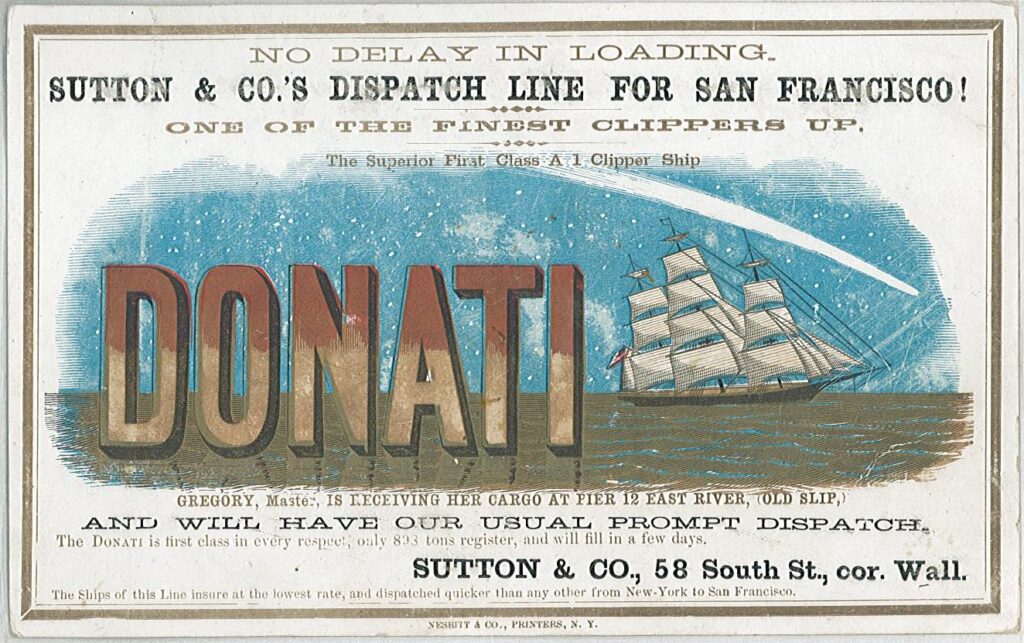

Clipper cards, sometimes called clipper ship sailing cards, are a unique type of advertising ephemera. They were printed as announcements that a particular ship, often a clipper ship, was about to sail. Along with providing basic information like the ship’s name, destination, captain, and pier, clipper cards were designed to be eye-catching in order to attract prospective passengers and merchants looking to ship cargo. As you can see, clipper cards often feature colorful and bold designs, sometimes with illustrations inspired by the name of the ship represented.

We still have printed advertising ephemera in our everyday lives. When I open my mailbox I can find half a dozen mailers for subscription boxes and local businesses. With that in mind, you might be wondering why anyone would be excited to find over 440 examples of 19th-century “junk mail.” What if I told you that, along with being beautiful examples of 19th-century design, clipper cards are incredibly rare?

One (19th-century) man’s trash…

There are a couple of reasons why clipper cards are so scarce. First, they were printed for a relatively short period of time. Clipper cards were printed from the early 1850s through the 1880s. Second, unlike the brochures in my mailbox, they weren’t printed by the thousands—clipper cards were printed for, and couriered to, a small audience of local shipping agents and merchants. Third, and finally, clipper cards were usually thrown away once the ship they advertised departed since they no longer had a purpose. Clipper cards were eye-catching and colorful, but they were printed with cheap materials at a low cost since they were ultimately meant to be discarded.

Since so few clipper cards were initially printed and even fewer survived, they have been valued as rare ephemera since the mid-twentieth century. Their value for collectors of ephemera has even led to modern, counterfeit cards being put on the market.

30 minutes of inventory can lead to 100 hours of work

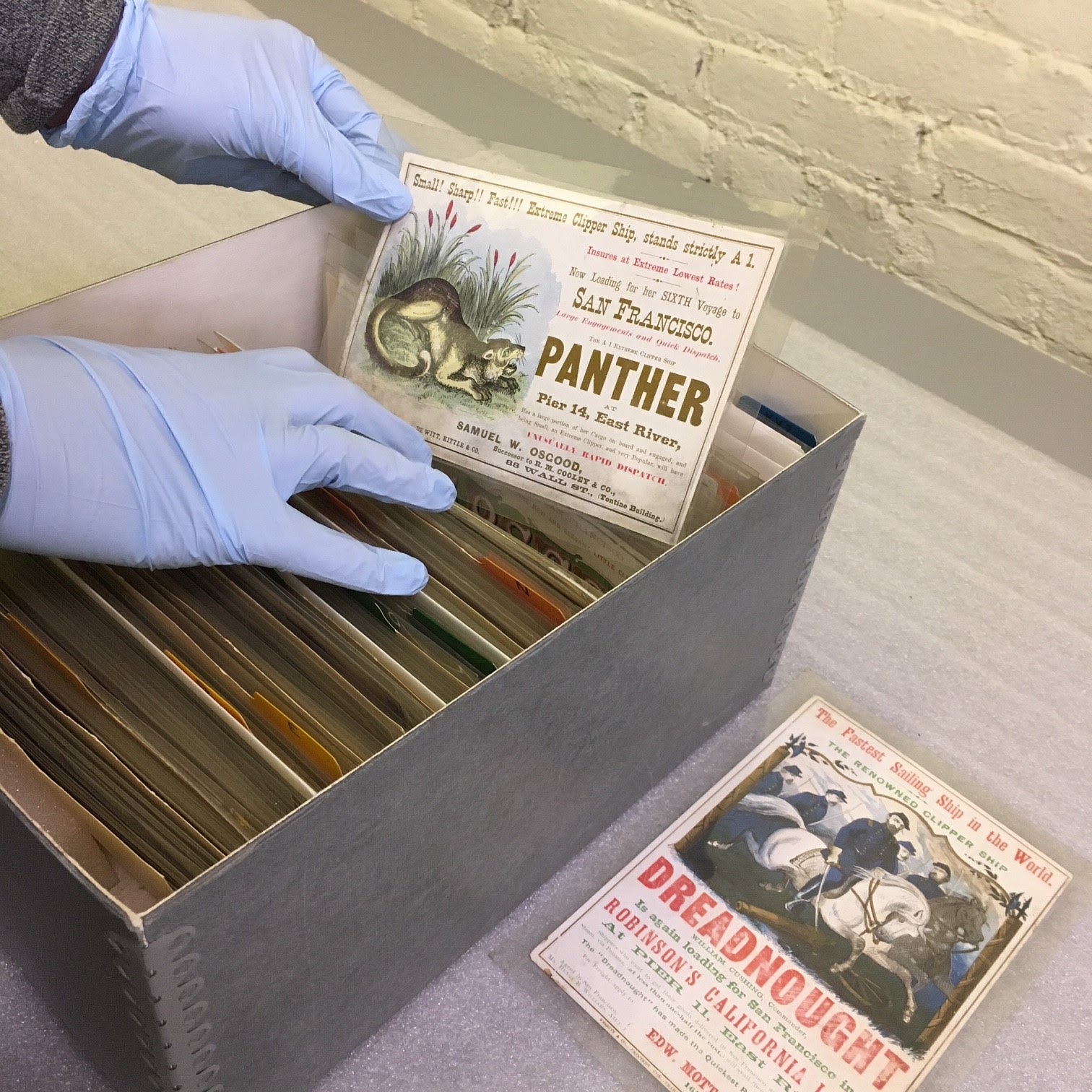

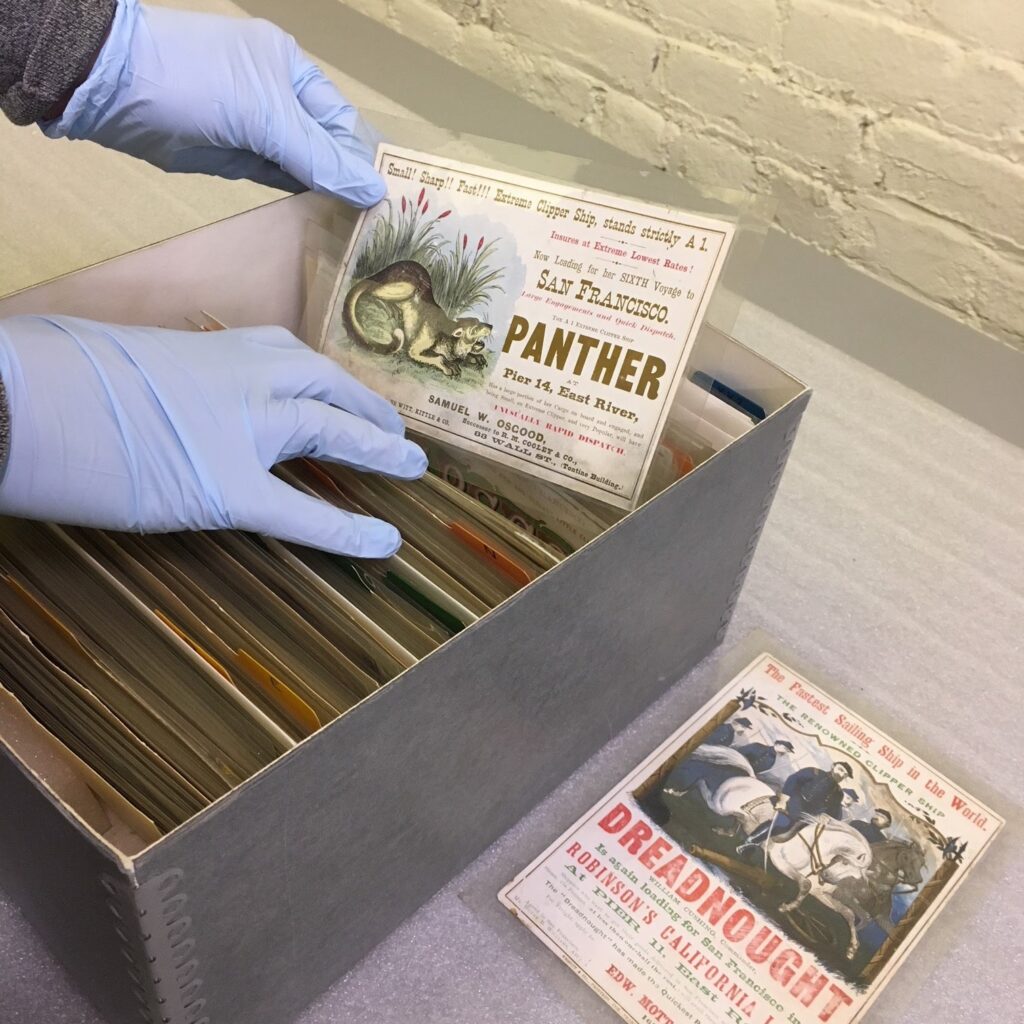

So how did I stumble upon such a valuable collection? During an inventory I came across a standard archival box with no label describing what was inside. Usually, the outside of a storage box has a label with a description or collection title, along with an accession or archival number; the tracking numbers assigned to collections objects to tie them to their documentation.

Accession numbers are especially helpful since they are the basis for our collection management database. Each accession number gets its own database entry that has all of the object’s information in an easily searchable format. In short—finding a box in collections storage with no label, and no numbers, means there’s going to be some investigating to do!

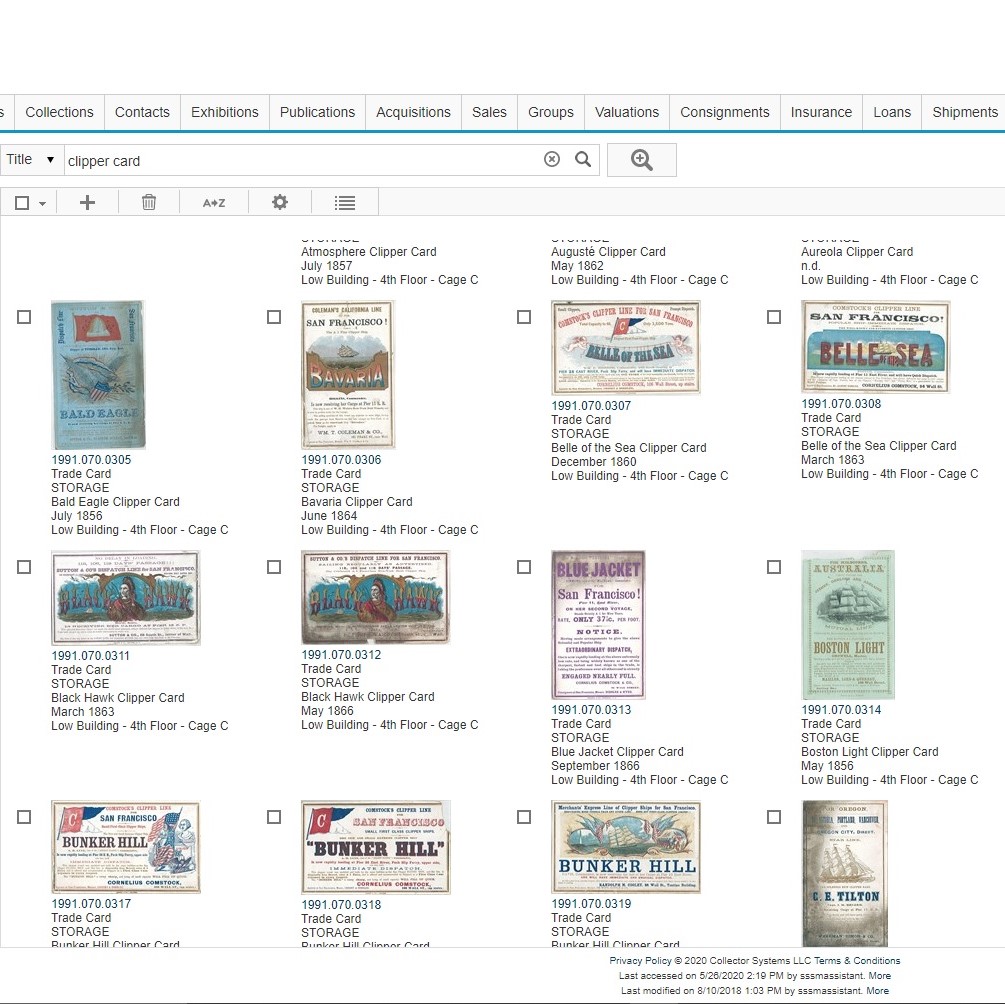

Thankfully I did have a lead: there was an old sticky note inside the box that read “Probably SBS.” Checking through database entries for the thousands of artifacts the Museum acquired in 1991 from the Seamen’s Bank for Savings (SBS), I came across a database entry and accession number for a collection of clipper cards! Unfortunately, the entry did not have a lot of information. There were no descriptions, images or even a count of how many cards were meant to be represented by the single accession number.

At this point we had to decide how we were going to move forward. If we wanted to fully integrate this collection of clipper cards into our database, and process them at “the item level”, this would mean assigning individual accession numbers to each card and then creating hundreds of new individual database entries.

These new entries would allow us to add tons of new information to the database for each card, including descriptions of each card’s illustration, names of printers and captains, and the advertised destinations. Additionally, each card would be easier to track.

Though there were obvious benefits to processing the clipper cards at the item level, it was also obvious that the project was going to take a lot of work. The staff time and resources could theoretically be used to complete similar, necessary work on other parts of the collection. Before my department could commit to the project, we had to determine if the clipper cards should be a priority for us.

“Value” in a museum’s collection

I’ve already described the rarity and value of clipper cards, but “market value” is far from the only consideration when deciding what is a priority in a museum collection. At our core, the South Street Seaport Museum is an educational institution. Our mission is to preserve and share the history of New York City as a world port, and how the city we know today can trace its origins and growth to the exchange of goods, labor, and cultures along our working waterfronts. The historic artifacts and records we have in our collection must support our mission. To put it simply, a collection of Botticelli paintings would be worth millions, but it would not be valuable in the South Street Seaport Museum collection since it does not connect to the history we are dedicated to preserve and interpret. In fact, caring for a collection of Botticelli paintings would take resources away from the history we want to preserve.

When it comes to collections priorities at the Seaport, clipper cards beat works by Renaissance masters any day of the week. So what do our clipper cards illustrate about the Port of New York in the mid-19th century?

Clipper cards, clipper ships and South Street

The most obvious topic this collection relates to is the development of the Yankee clipper ship. A clipper ship is a sailing ship designed for speed at the expense of cargo space with a thin, “sharp,” hull and three square-rigged masts. The first clippers had been designed in the mid-1840s for the China trade[1] “Development of the Clipper Ship” by Charles E. Park published by the American Antiquarian Society 1929, p. 59 , but the clipper ship design became incredibly popular during the California Gold Rush. Clippers were the fastest in ship design and prospectors (along with merchants making money supplying prospectors) were “rushing” to California as quickly as possible. Between 1850 and 1854 over 100 clipper ships were launched.[2] “The Flying Cloud and The California Clipper Fleet,” California History Nugget: Devoted to the Story of the Golden West, Volumes 1-5 California State Historical Association, 1924, p. 216

As the largest and busiest port city in the United States, New York City was the gateway to California by sea, and the clipper ships were departing from the piers of South Street. Nearly 75% of the clipper cards in the collection are advertising voyages from New York to California, and the majority of piers listed are East River piers 15, 16, and 17 (which were located close to their contemporary iterations.)

Romance Of the Sea Clipper Card, December 1860. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum, 1991.070.0628

Aside from generally documenting an important freight and passenger trade for New York City, the clipper cards have a wealth of printed information meant to advertise the merits of the ship. The text often boasts about the clipper’s fastest journeys (only 89 days!), who built the ship and where, and how passengers could book passage with New York’s shipping agents.

Clipper cards…and printers?

The demand for the clipper ships slowly waned with the close of the Gold Rush in 1855. There was still demand for transport between New York and San Francisco; new Californians needed a variety of goods and their exports of wheat and lumber made shipping to-and-from San Francisco a frequent route. However, speed was no longer the priority it had been during the “rush,” and sailing ship designs that allowed for more cargo became popular. Steamships, and later railroads, were also burgeoning alternatives.[3] “Development of the Clipper Ship” by Charles E. Park published by the American Antiquarian Society 1929, p. 75 With fierce competition for cargo and passengers, clipper ship owners needed effective advertising. Enter the clipper card, now viewed through the lens of graphic design and printing history.

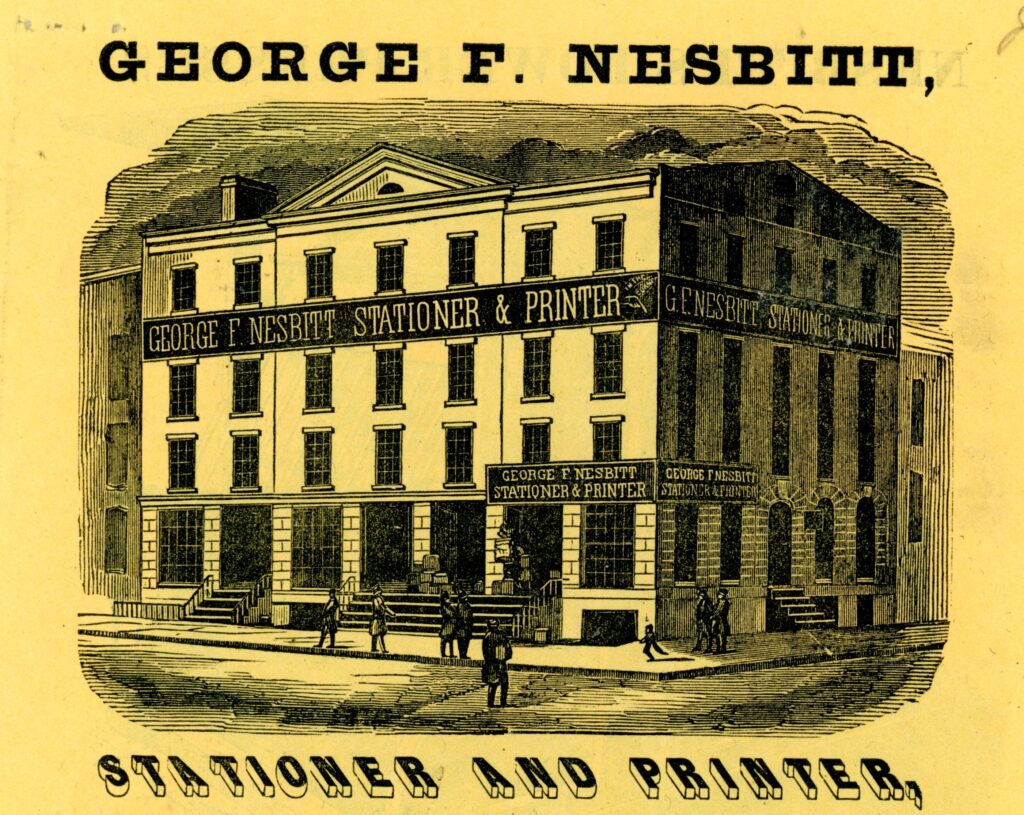

Clipper cards are perfect examples of 19th century job printing and how it flourished in New York City due to the port’s bustling trade. Vessels needed bills of lading, customs needed certificates and forms, ferries and passenger ships required tickets, and every business needed advertising be it handbills, pamphlets or indeed clipper cards. At the Museum we sometimes have to explain to visitors why we have our letterpress print shop, Bowne & Co., on our campus, but job printing is integral to the economic ecosystem that sprung up around the South Street piers. Clipper cards are especially significant to the history of New York City printing since some of the earliest known cards are by a New York City printer, George F. Nesbitt (1809-1869).

120 years of provenance

After our clipper card research, we determined that this collection should be accessioned to the item level since the cards have incredible meaning for the history of New York’s port industries. We committed to assigning them individual numbers and individual database entries. You would think that now we could get to work scanning the cards and doing some simple (if extensive) data entry? Nope!

Before processing the cards, and passing them to the Museum’s Assistant Registrar to assign them numbers, I had to understand how they came into the Museum’s collection. Tracing the collection’s provenance is a critical step since we don’t want to lump together cards that came from different donations, and we need to know that we had the complete collection in front of us before assigning numbers. We had to know that we weren’t overlooking other clipper cards still waiting to be found in our storage areas.

When I failed to find an inventory of the collection in the original database entry, I figured there may still be an inventory in the hard-copy files related to the acquisition of the Seamen’s Bank for Savings Fine Art Collection. The issue is I didn’t find one—I found several. This collection had passed through a few institutions over a period of 120 years before arriving at the South Street Seaport Museum. Unsurprisingly, there were missing records and some gaps in institutional memory.

Owner no. 1 was none other than George F. Nesbitt, innovator of clipper card production, and one of the greatest successes of maritime job printing in New York City. Nesbitt was always located somewhere between the financial district and the busy piers of the East River, and he specialized in printing for shippers and ship financiers. By 1869 his company had dozens of employees and would remain in business until 1912.[4] “The Story of the House of Nesbitt”, by L.G. Quackenbush The Philatelic Gazette, Volume 3, 1913, p. 230 Though we don’t have records of the donation, at some point Nesbitt’s company presented a collection of clipper cards to the Seamen’s Bank for Savings.

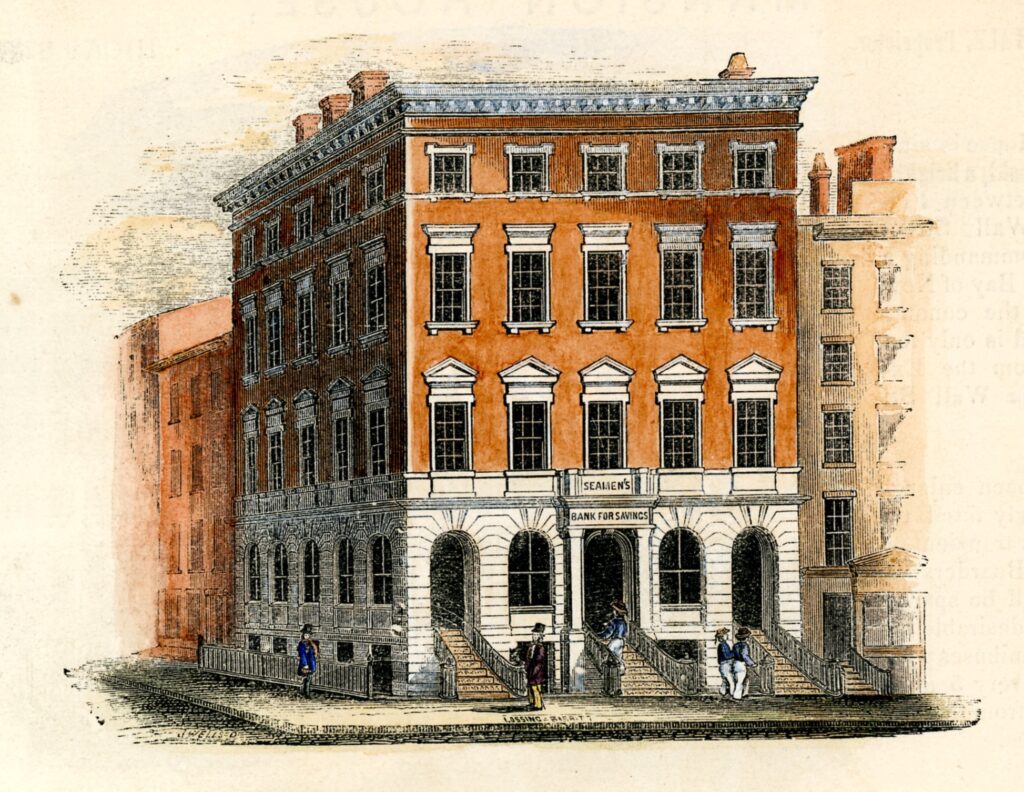

Owner no. 2 was the Seamen’s Bank for Savings, established in 1829 with the purpose of having depositors that were exclusively seamen and mariners. They opened up to the general public in 1833 but retained a nautical public image to attract sailors as depositors. They became well known for their collection of maritime art in the 20th century.

The origins of the Bank’s Fine Art Collection is murky since they were not primarily an art collecting institution, but it is known that by the 1870s the bank had a collection of ship models. By the 1920s and 30s the bank was using both its art collection (which included paintings, scrimshaw, and fine art prints) for publicity and promotional projects. Their collection was used for bank décor and for reproduction in advertising and memorabilia. In fact the Curatorial Department, when it was professionalized, was administered by the Advertising Department until they were merged in 1986.

Like much of the fine art collection, there is little documenting when and why Nesbitt & Co. gave the clipper card collection to the Bank. I’ve found no mention of the relationship between the two organizations, and there is no exact date for the gift. From the wording of the one document that notes the acquisition, it sounds as though the collection was presented before Nesbitt & Co. went out of business in 1912.

The clipper card collection isn’t mentioned until 1944 in a general article about the SBS’s collection, but there was no additional information. Another article, printed in 1949, stated that the collection consisted of about 750 cards. When I read this my heart stopped; was I missing another 300 clipper cards somewhere in the Museum’s storage?

Further research showed the clipper card collection did not remain static at the Bank. SBS would continue to purchase new clipper cards along with occasionally selling cards in their collection. There is better documentation as to what was purchased than what was sold, but we know in the 1980s the Bank began selling off large parts of the collection. In 1982 alone the Bank sold 286 clipper cards from the collection. The sale was noted, but the contents of the sale were not recorded. At the very least I knew that I wasn’t missing 300 or so clipper cards.

The SBS records also noted that the collection had originally been presented by Nesbitt & Co. in 17 volumes, with the cards pasted into books. Frustratingly, there was no record of the original arrangement of cards within the books. If we had been able to confirm the original arrangement, we would have assigned them accession numbers in that order.

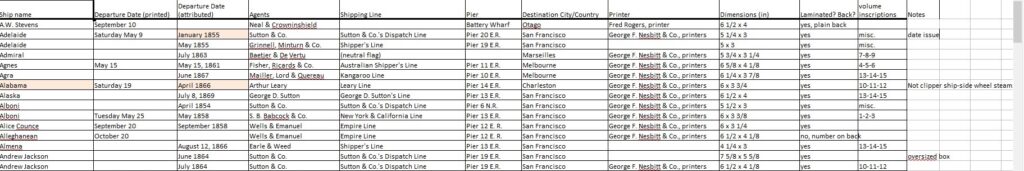

When I finally collected every piece of documentation, I realized there was no singular inventory I could follow to confirm the contents of the collection and assign accession numbers. I would have to transcribe the data on each inventory into a format where we could compare them easily and determine if anything was missing and if any clipper card was definitely not from the SBS acquisition. Enter the spreadsheets.

Processing

Perhaps in another blog post I will go over the massive spreadsheet that was made for the 449 cards in the collection, and how they were tracked over the 5 inventories we had on file, but let’s skip the riveting story of how I filled out over a thousand-cell excel sheet.

After we triple checked we had the complete collection, we used the same spreadsheet for the initial data entry. Ultimately, the project took several months and a dedicated registration intern transcribing the information on the cards themselves including ship name, departure date, shipping agent, printer, port of departure, and any other subjects. When the information was added to the database, this same intern uploaded scans of the cards, added descriptions of the cards illustrations, along with each card’s dimensions and a summary of the card’s physical condition.

Again, this is why we really had to be sure we could justify that the clipper card collection was worth the commitment of staff time and resources to process!

Results

Aside from achieving a new level of collections care and intellectual control over the clipper card collection, the inventory project has resulted in some exciting curatorial opportunities.When it comes to the many stories we interpret for our visitors, there is a clipper card for nearly any occasion. We now know how many of our clipper cards are related to the Civil War, to the rise of steamships, and to dozens of 19th century events and cultural touchstones from the passing of the Donati’s comet to famous opera singers.

With the information and images of the cards in the database it doesn’t have to be someone like me, who has been working with the collection for years, finding the connections. A few months after the project was finished, a new collections and curatorial intern that had no familiarity with the clipper card collection or with the Seamen’s Bank for Savings art collection as a whole, suggested that we use a clipper card for a social media post she was writing. The fact that she found a card related to her research on the database within a few minutes, demonstrated how accessible the collection had become. At the end of the day, that is why we care for our collections in the first place: so that we can share them, and their history, with the world!

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | “Development of the Clipper Ship” by Charles E. Park published by the American Antiquarian Society 1929, p. 59 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “The Flying Cloud and The California Clipper Fleet,” California History Nugget: Devoted to the Story of the Golden West, Volumes 1-5 California State Historical Association, 1924, p. 216 |

| ↑3 | “Development of the Clipper Ship” by Charles E. Park published by the American Antiquarian Society 1929, p. 75 |

| ↑4 | “The Story of the House of Nesbitt”, by L.G. Quackenbush The Philatelic Gazette, Volume 3, 1913, p. 230 |